I contend that you have not meaningfully defended your ideas from certain specific and repeated criticisms I've made. I assume that you are arguing in good faith, but your responses have consistently failed to address direct questions and the various passages I've written to explain my position. It's unsurprising that you would feel like no progress is being made when you consider that you have not engaged the main thrust of my argument.

The key item that I have yet to see you touch upon is the implication of your first premise on our knowledge of the universe. Do you acknowledge or do you dispute that if we accept the premise "It's possible we're in a simulation," that this implies that we cannot know anything at all?

I think what you say here further belies the fact that you have not been following along. Unfortunately, it also reveals a predilection for fallacious reasoning. I'll address these two parts separately.

Regarding the former, I do not claim that we do not actually have awareness. I do not even know what it would mean for my apparent sense of awareness to be false. You, however, have put forth the premise "It's possible we're in a simulation," which bears the implication that nothing is knowable for sure, even our apparent sense of awareness. I think you must be confusing my personal beliefs about the apparent universe with the necessary conclusions that result from accepting

your first premise. In simple terms, I'm not telling you what

I believe about awareness, I'm telling you about the implications of accepting

your premise.

Regarding the latter, it is troubling in the extreme that you would first raise an appeal to authority and an appeal to the people (both well-known fallacies) and then go on to defend those appeals. It's also mildly disturbing that you seem to be making a sideways allegation that I claim any level of authority on this or any other subject. I do not.

The number of people who espouse an argument has no influence on the truth or falsity of that argument. You might appreciate that I have not criticized your arguments on the basis that nobody has echoed them or expressed support for them. Arguments stand on their own, regardless of how many people are making them or what famous people support them.

It is patently false that "things are more likely to make sense if a lot of scientists accept it". It is also false that an argument requires the support of an authority in order to be true or to be worthy of consideration.

I'm not particularly inclined to go on about the reasons why appeals to authority and appeals to the people are fallacious forms of reasoning because others elsewhere have already done a nice job of explaining them and you can easily google "argumentum ad populum" and "argumentum ab auctoritate".

excreationist said:

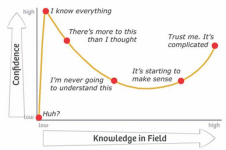

Perhaps this graph applies to your level of expertise in this area:

I'm going to assume, rightly or not, that this comment and the accompanying graph were posted in jest.

excreationist said:

I tried to use normal reasoning with you but like I said I've been getting nowhere at all.

I, again, contend that you have not. Reasoning with me would require you to directly engage the arguments I'm making. One, in particular, about the necessary implications of your first premise, has been untouched by you and is the perfect place to start. "Normal" reasoning, in my humble opinion, should also exclude fallacious forms of reasoning like appeals to authority and appeals to the people. It is well-established that the truth of something is independent from who or how many people put their name behind it.

Let's talk about your argument, not what famous people or lots of people think.

excreationist said:

Since I haven't argued against that before and it is interesting I will attempt to respond to this...

So how would it work? Let's say they had two seemingly equal groups of circles.... they count the first group while pointing at the circles - "1, 2". Then the second - "1, 2". Then they try to count them all while pointing to each circle: "1, 2, 3, 3" or "1, 2, 3, 5". Or they could go "1, 2, 3" while skipping a circle (with no-one ever realizing) - or "1, 2, 3, 4, 5" while always counting one circle twice. Or a circle appears or disappears when they are counting them all (but there are two lots of two when they are doing the first part (2 + 2)).

That also implies that 2,000 + 2,000 is not 4,000 - instead it would agree with the first method.... so it would be 3,000 or 5,000 (or whatever the answer you're trying to trick them with).

Even if you can argue that this is possible, how likely is it? How much demand is there for simulations that trick all of the people that 2 + 2 is something else other than 4?

Perhaps you'd say that we can't know how likely it is and that it could be quite likely....

I think it is quite easy to imagine how numbers and arithmetic could be a deception if one were in a simulation. Let's use another video game example since they seem so well-suited to discussions about inside and outside worlds.

Let's say we live in the world of a video game and, within this world, there is a crafting system. In this crafting system we can combine objects (as an analog to addition) to create new objects. By observing our game world and experimenting with recipes we could learn all of the relationships regarding which objects combine and how. It would be impossible within this game world to dispute that, for instance, three medical herbs combine to become a healing potion. It would be demonstrable and directly observable, just like arithmetic functions appear to us. From outside of the video game it is plain to see, however, that the crafting system is arbitrary and that there is nothing that would prohibit us from programming the game so that it took four medical herbs to make a healing potion instead of three. Denizens of such a world have no way of discerning whether the rules of the crafting system are necessary or arbitrary.

Interestingly, there are even examples of crafting systems in games that are internally inconsistent or "broken" in the parlance of gamers. Consider the recently released game Cyberpunk 2077. In that game, items can be dismantled into components which can then be reassembled into new items. However, due to the way the crafting system was arranged, it is possible to take items that are worth some amount, dismantle them, re-assemble them into new items and sell those items for a more than what the original items were worth. Simply put, you can get more out than you put in and exploit the system to generate infinite cash.

The rules and properties associated with numbers and the operations we can perform on them are discoverable to us but there is nothing that prohibits them from being different, being inconsistent or changing. We've never observed that to be the case in our world, but by looking at worlds which we simulate, it's clear that we could assign properties and relationships on a purely arbitrary basis. We could make a simulation where 2 + 2 = 4, except on Wednesdays. We could program a simulation where the quantity of objects is constantly changing every time we count them and where mathematical operations have randomized or otherwise unpredictable results.

If it's possible that we live in a simulation then it is possible that what we observe, such as 2 + 2 = 4, is just made up and doesn't have any correspondence with how the outside world works. There's no way of determining how likely any given arbitrary system is either. What's the likelihood, for example, that a simulation designer would require three herbs to make a potion versus, four or five or any other number? It's absolutely unknowable and can't even be guessed at.

The same is true for any observation made from within a supposed simulation. There is no guarantee and certainly no way of ever proving that what is observed within the simulation correlates in any way with the outside world. As such, all observations, statements, arguments and so on, must be qualified as being potentially wrong, absolutely unproveable or, equivalently, simply left unsaid.

For that reason, I assert that we must reject the possibility of being in a simulation. Without this rejection we are forced to remain silent about the universe and our experiences within it.

As such, I can happily accept your first premise for the sake of argument, but by doing so, the conversation, for all practical purposes, ends.