Read an explanation of Fractional Reserve Banking, what you have as support to claim that the banks loan out deposits. Search for yourself and find a source that you trust. (Wikipedia has in the past had a good one, but I am reluctant to suggest one any more because other people, not you, just use it as an excuse to ignore what the reference says and to attack the creditability of the source.)

The explanation that you find will say something along the lines of that the bank needs to be able to cover some percentage of its volume of loans with deposits. The explanation will probably use some percentage that makes the math easier, say 10%. But the Fed only required 3 to 8% only when FRB was in force.

No explanation of FRB that I saw told where the other 90% or 97% or whatever comes from.

A very large bank, the member banks of the system, have a reserve account belonging to Fed, which the bank loans out and deposits the loan repayments back in. Smaller banks have similar reserve accounts from member banks. If this account is drawn down to zero the bank goes to the Fed who creates money together with the Treasury Department to replenish it. This is the money created out of thin air, money created to satisfy the demand from the economy for it.

Congress made FRB moot when responding to requests from the banking industry they made commercial demand accounts exempt from the requirements to be used to cover outstanding loans, i.e. 0% had to be held as reserves. Commercial demand accounts, mainly checking accounts for payrolls and to cover daily operations, are the majority of the deposits in the banks.

What they replaced FRB with was a requirement that a bank could only have loans outstanding equal to a multiple of its capitalization, at first it was 10 times but Congress lowered it to 8 times in the aftermath of the Great Recession.

So now 100% of the money that the bank loans out is money that was created by the Fed or money from the interest charged by the banks to cover loans that defaulted, to replace money that was created by the Fed.

What you are describing is well known, economists call it the velocity of money. It is as you say, a single dollar changes hands multiple times in a year growing the GDP by a dollar every time it is exchanged. What it doesn't do is count as an additional dollar in the money supply every time it is exchanged.

Once again, I urge you to search for "what is the velocity of money," pick a source that you trust, and see if it is what you are describing above.

The money supply is also well known. Search for "what is the money supply M1" or M2 or M3 or "Currency in Circulation" or "monetary base." They are different methods of counting different bank accounts as part of the money supply. These are made up of "Currency in Circulation" and money in various bank accounts.

Only "Currency in Circulation" (CURRCIR in FRED if you want to see a chart of it) is impacting the economy. Money in a bank account has no impact on the economy. Like everything in mainstream economics, there is a lot of voodoo about which measure of the money supply reflects the impact of money on the economy.

Interest rates control the velocity of money because they cause a change in the number and amounts of loans that directly create money, that put money that was doing nothing for the economy sitting in a reserve account and put it back into the economy. Unfortunately, as interest rates are effectively below zero in relation to the rise in the cost of living and the indexes of business costs, the amount of control the Fed has by adjusting the interest rates is nearly zero.

A much better way is to directly control the amount of money in the economy by using a variable tax rate controlled by the Fed. If we have inflation, increase the taxes withheld by the payroll tax, for example, and put the money from it into the document shredder. If you have deflation in a recession lower the payroll tax and the withholding for it and have the Fed create money to replace the lost taxes in the Social Security and Medicare and Medicaid trust fund.

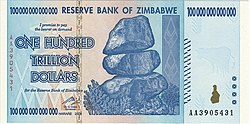

It should be determined by the demand. So far, in the US it has been. In places like the Weimar Republic and Zimbabwe it was used to fund government spending, with catastrophic results.

The other way that money is created is by the federal government putting its budget into deficit. It has been used recently primarily to give tax relief to rich people. When the budget deficit is given to the bottom 90% of earners they tend to spend the money into the economy and the economy's reaction is positive growth that reduces the impact of the deficit. When the money that is created by the budget deficit is given to the very rich they tend to save the newly created money in stocks and bonds where there is no impact on the overall economy. No impact no growth.

The refusal of mainstream economics to see the effects of income distribution is intentional. The rationale for using neoliberalism rather than reality-based economics as our political economics is to reinstate the importance of the already rich to the economy whether it actually exists or not.

In both the case of Weimar Germany and Zimbabwe the budget deficit wasn't used to finance government expenditures inside the respective countries, the money created went out of the country, to pay reparations for WWI in the case of Germany and to import food in the case of Zimbabwe to make up for a disastrous farmland redistribution policy. Money that leaves the country creates deflation.

Why did Congress do something as stupid as to declare derivatives to be forever free from regulations?

Yup, this is a big problem. In 1929 we learned the risk of allowing margin buying with too high a ratio. We quite sensibly addressed it by putting a limit on margin ratios. However, while derivatives are not loans they suffer from the same sort of problem that they can cause instability when the market changes--and it's no surprise they eventually blew up. (Yes, you can point to other factors that triggered it--they were TNT, not the blasting cap.)

Correct.

Why weren't the bankers who were responsible for the collapse of their own banks by their clearly criminal behavior not arrested, convicted, and imprisoned?

Because it's extremely hard to prove that any given banker engaged in a criminal act.

Partially correct.

After the first much smaller deregulation delusion crisis, the Savings and Loan fiasco, over a thousand bank officers were convicted and sent to prison. The reason that only a handful of bank corporate officers went to prison after the deregulation delusion II crisis was because the very first order of business for Newt Gingrich and the Republican Revolution Congress in 1995, before any of the Contract with America was even considered, was to pass a law giving effective immunity to corporate executives for crimes committed by the corporations. They repealed the laws that sent the S&L corporate officers to prison.

So with no laws, it made it hard to prove criminality.

Once again, the answer is simple. We had to bail them out because what they do is vital for the economy. In our real economy, the government is responsible for the governance of the banks. The banks don't self-regulate, obviously.

The problem is the banking system lacks the ability for a company to go bankrupt and have its shares turned over to creditors but continue to operate. Bail them out, take the shares and trickle them back onto the market at a set rate.

Half credit for this answer. The only creditor for a failed bank is the Fed and the FDIC, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

There is a procedure for a failed bank. The bank is liquidated and the assets are used to pay the depositors and probably the deposit insurance company for returning their money. The assets of the bank, the checking and savings accounts are sold to a larger bank that opens the bank for business the next day.

The full credit answer would be because the banks that failed were so big that no one could take them over, except the government which the neoliberal Bush II administration was reluctant to do, literally they were too big to fail. It was a very bad idea to let them get so big, it was a very bad idea to tear down the wall between consumer/commercial banking and investment banking, it was a very bad idea to allow national banks instead of regional and local banks, and it was a very bad idea to let banks own stock brokerages and insurance companies. These bad ideas came from a single source, neoliberalism, and its idea of deregulation.

In fact, there is a good argument for the federal government to provide consumer and commercial banking directly by setting up postal banking or by other means. Since banks have been largely deregulated, government direct banking could force the banks to charge lower interest in the best way that capitalism provides, through competition.

The government rates are not going to be set by market forces. Public-private competition is generally a bad thing because the government business operates more from ideological rules than financial ones.

That taste in your mouth that is turning fatally soar is Kool-aid if you think that the interest rates on debt are set by market forces today. If any bank realizes they are charging a lower rate than other banks the most probable outcome is a rate increase by the bank charging the lower rate, not a decrease by the banks charging higher interest rates.

Although I do have to admit that my suggestion about the government competing with private banks to replace banking regulations was meant to be provocative and not serious, especially in these days when Wall Street owns one political party outright and one half of the other one.

But the government shouldn't be cowed into not running consumer and commercial banks in cases where the private banking system is not providing the needed services to a geographic area or to a segment of the population. AOC is correct that the poor are not well served by the banking industry. It is just that there is more profit in writing one $500,000 mortgage in the suburbs than there is in writing ten $50,000 mortgages in the city. And there is no reason to believe that the banks serving the poor would lose money, especially a low overhead operation like a postal or internet bank.