Swammerdami

Squadron Leader

Ringe, for his classification of IE languages, identified grammar features that were UNLIKELY to be borrowed.

(If interest I'll try to hunt a reference.)

(If interest I'll try to hunt a reference.)

Basque (Pyrenees, SW Europe)Bangime is classified consistently as Dogon in the Lexibank model (95%) and as Mande (66%) or Atlantic-Congo (29%) in the Grambank model. Consequently, the combined model primarily has Bangime unclassified (86%).

Kusunda (Nepal, Himalayas)Basque on the other hand remains mostly unclassified in both the Lexibank (46%) and the Grambank model (47%), although the latter also tends to propose an affiliation with Sino-Tibetan (39%). The combined model proposes an affiliation with Indo-European (23%) or Sino-Tibetan (18%) but also includes the unclassified affiliation (32%).

Mapudungun (SE S America)In the Lexibank model, Kusunda is affiliated either with Nuclear Trans-New Guinea (51%), Austroasiatic (19%), or left unclassified (17%). The Grambank model mostly affiliates Kusunda with the Sino-Tibetan family (60%). The combined model mostly proposes no affiliation of Kusunda with other language families (79%).

Mapudungun is split between several language families in the Lexibank model: Timor-Alor-Pantar (29%), Austronesian (18%), or Unclassified (11%). The Grambank model mostly suggests a Salishan affiliation (68%) or no affiliation (17%). The combined model, again, finds no clear affiliation pattern (88%).

I've seen Basque proposed to be recognizably related to Indo-European, but that seems to me very unconvincing. Stronger IMO is its being related to North Caucasian, at least according to John Bengtson's work. JB pointed out cognates in highly-stable vocabulary, and at least in this test, Euskaro-Caucasian seems about as strong as Indo-Uralic.The closeness between Basque and Indo-European suggested by the combined model has been recently suggested using both traditional and computational methods Blevins (2018); Blevins and Sproat (2021). The connection of Basque with Sino-Tibetan suggested by the Grambank model and the connection with Nakh-Daghestanian suggested by the Lexibank model would fit with the far-ranging proposal of a Sino-Caucasian macro-family, in which scholars at times include Basque (Starostin, 2017).

That's why long-rangers focus on lexicon -- it's hard to find very long-lived bits of grammar.From our findings, we can make three conclusions, (a) language affiliation achieves promising results even for language relations way back in time, (b) grammar alone is not sufficient for a successful affiliation, and (c) combined models seem to work very well, reflecting that languages are best affiliated by using lexicon plus a bit of grammar.

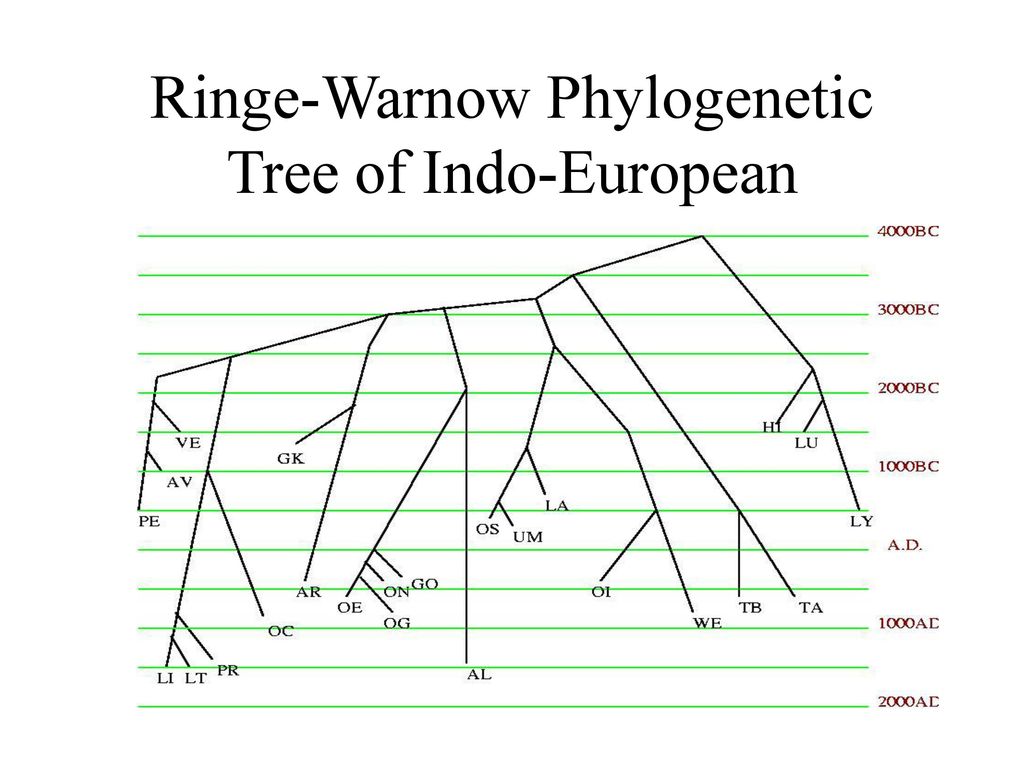

Indo-European and Computational Cladistics by Don Ringe, Tandy Warnow, and Ann TaylorI've always been most impressed by the methods and results of Ringe and Warnow. I attach their proposed chronology below.

I see that the initial split in Italic between LA (Latin) and OS-UM occurs at 1300 BC, exactly as lpetrich proposes.

Is it this paper? Indo-European and Computational CladisticsRinge, for his classification of IE languages, identified grammar features that were UNLIKELY to be borrowed.

(If interest I'll try to hunt a reference.)

Morphosyntactic: about morphology (word forms) and syntax (word arrangement)Importantly for historical linguistics, that process is tightly constrained; for instance, the system of morphosyntactic categories is normally mastered by age four, and native acquisitionof a language is virtually impossible after the onset of puberty.

andMoreover, it appears that every successful acquisition of a native language gives rise to a robust grammatical 'signature' which persists throughout life. The most important details and their consequences can be summarised as follows.

Recent research on native-language acquisition by children shows that the contrastive system of sounds, the inflectional morphology and the basic syntax of a native language are acquired in the first six or seven years of life, and that `mixed' grammars are not acquired even in multilingual environments.

andRecent research in sociolinguistics shows that, while most linguistic structures can be borrowed between closely related dialects, natively acquired sound systems and inflections are resistant to change later in life; attempts to acquire a non-native phonemic contrast, phonological rule or inflectional category are at best only partly successful.

"... one often encounters claims that practically anything can be borrowed into one's native language in a suitable bilingual situation." But that looks at results rather than process.Borrowing between speechforms that are not very similar appears to be even more severely constrained, as one would expect. Studies of the bilingual situations in which borrowing occurs show that the phonology and morphosyntax of one's native language are typically carried over into a language learned later in life, but not usually the other way round.

Like Hebrew plurals in Yiddish, a dialect of German.... morphosyntactic structures even of very dierent languages can apparently be borrowed into a community's native language in the context of community-wide bilingualism persisting for many generations.

That native language as a second language for some speakers of it.It seems likely

that some ®rst-language learners in such situations misinterpret frequent code-switching as monolingual behaviour and thus learn foreign morphosyntax as part of their native language, and that, given enough time, their analysis can become dominant in the community. However, we must also note that the only study in depth of such a process in progress concludes that even morphosyntactic borrowing of this kind is mediated by lexical borrowing: in effect, 'core' lexemes are borrowed and bring their morphosyntax with them.

...

A surprising number of examples of the supposed borrowing of foreign morphosyntax by native speakers can be reinterpreted rather easily as the influence of a native language on a second language.

The article quoted several examples.For instance, borrowability hierarchies lead to predictions that unbound forms are more borrowable than bound ones, lexical items more borrowable than grammatical items, semantically transparent forms more borrowable than semantically opaque ones, etc.

This database also includes semantic shifts. This is necessary for long-distance comparisons, to increase the amount of data available.The 400-item list is a planned expansion to the more "traditional" 100- or 200-item Swadesh wordlist. It is designed as a fixed, relatively universal set of discrete semantic notions, lexical equivalents to which can be located in all or most of the world's languages and reconstructed to all or most protolanguages for which sufficient data from descendant languages are available. (Relatively is an important word here, since even the much condensed 100-item wordlist is known not to be 100% universal, much less so any expanded version of it; nevertheless, at the very least the lexical items found on the list correspond to objects, processes, and qualities found across all of the world's regions and possibly pertaining to all types of societies).

Thus trying to keep the semantic spread from being too great, for maintaining falsifiability. Something additionally useful would be to have an estimate of how many times each shift has happened in one's reference sample. One can then weight an amount of semantic match by how common a shift is.List of basic semantic concepts (from the same 400-item list) that are known to be connected to the current meaning through "trivial" semantic connections (relatively simple metaphors and metonymies, synchronically or historically attested or reliably reconstructed for at least two or more linguistic situations).

It's still a work in progress, and all commentary in the database is still only in Russian, though the authors hope to eventually make English versions.N = "noun" (186 terms), V = "verb" (132 terms), A = "adjective / descriptive verb" (63 terms), P = "pronoun" (13 terms, including personal, deictic, and interrogative pronouns), Q = "quantifier" (5 terms, including numerals and such quantifier terms as 'all', 'many', etc.), C = "particle / clitic" (only for the word 'not').

ProposesAbout THIS THING

A page that looks at historical linguistics (with a focus on the Afroasiatic Hypothesis of the origin of Proto-Indo-European). I occasionally delve into interesting parts of history, generally interesting stuff, and of course a bit of nonsense.

That latter time is around when Turkic speakers started spreading out of their Central Asian homeland.The hypothetical Altaic a.k.a. Transeurasian macro-family consists of the nuclear families: Turkic, Mongolic, Tungusic, and the outliers: Korean and Japonic. The genealogical relationships between Turkic, Mongolic, Tungusic are obscured by prehistoric and later contacts. The working hypothesis of our Moscow team is that the genealogical filiation is [Turkic [Mongolic, Tungusic]] with intense post-split contacts between Turkic and Mongolic in the 1st millennium BC.

Altaic and Vasco-Caucasian are both Early Holocene, and that would make Indo-Uralic also Early Holocene.1. All formal tests dealing with «core» basic lexicon indicate a connection between Proto-Indo-European and Proto-Uralic.

2. The simplest and most logical explanation of this connection, given the nature of the data, is descent from a common ancestor.

3. Comparison of «automated» vs. «manual» results shows that the «strength» of the binary Indo-Uralic connection is more impressive than the «strength» of the larger Nostratic hypothesis, but is formally comparable with the «strength» of such deep level connections as Altaic or Vasco-Caucasian.