Potoooooooo

Contributor

https://daily.jstor.org/why-are-medieval-lions-so-bad/

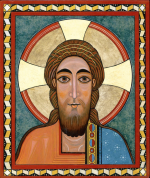

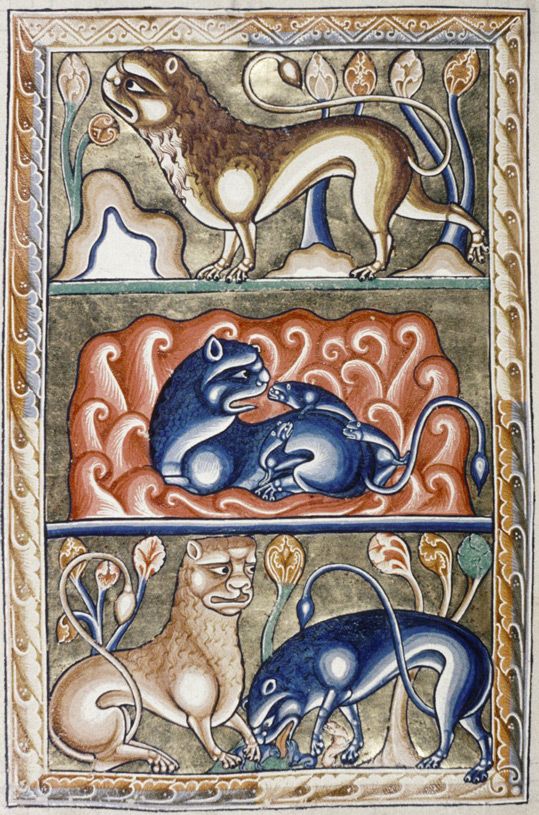

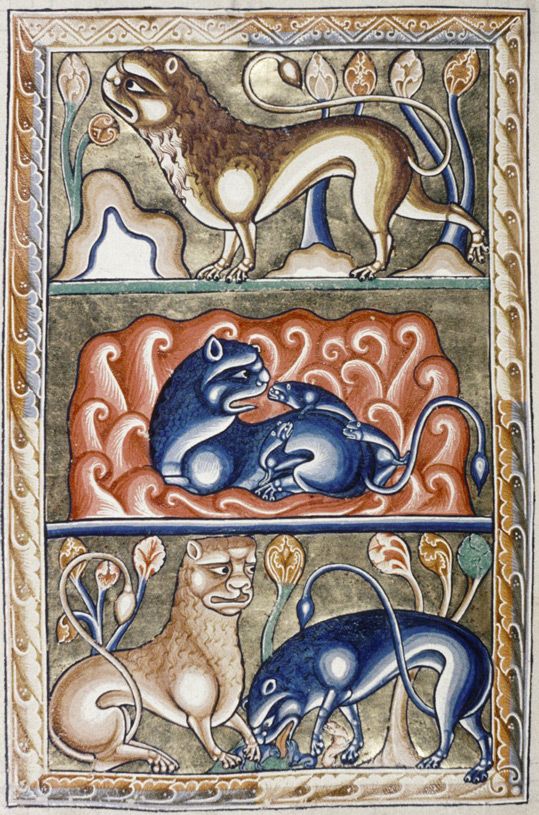

On the popular Twitter hashtag #notalion, medieval historians and aficionados share the most un-leonine lions from the Middle Ages. One on the edge of an illuminated manuscript smiles gently, its flat face almost human; another from the eleventh century seems to smirk with pride at the glory of his mane that radiates like the sun.

Why do these lions look, well, not like lions? Scholar Constantine Uhde wrote for The Workshop in 1872 that in early Christian and Romanesque sculpture, “the physiognomy of the lion gradually loses more and more of its animal aspect, and tends, though quaintly, to the human.” The obvious explanation is that there weren’t that many lions in medieval Europe to model for artists, and the accessible representations for copying had the same lack of realism.

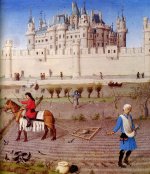

As art historian Charles D. Cuttler writes in Artibus et Historiae, however, there actually were a number of lions on the continent, imported from Africa and Asia: “There are many accounts of their presence and even their breeding, first at various courts and then in the cities; they were kept in Rome by the popes as early as 1100, and Villard de Honnecourt made a drawing of a lion ‘al vif’ [‘from life’] in the thirteenth century—where he saw the animal is unknown.”

The city of Florence had lions in the thirteenth century; lions were at Ghent’s court in the fifteenth century; and a lion house was built at the court of the Counts of Holland sometime after 1344, so it’s not impossible that first-hand accounts of lions were available to artists.

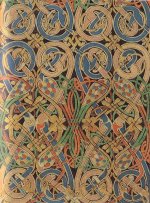

The inaccuracy of medieval lions may have been a stylistic preference, particularly in a bestiary, or compendium of beasts. “Because the artists chose to illustrate the animals rather than their accompanying moralizations, they had more freedom of choice in their imagery: the bestiaries provided them with more latitude for the expression of design and other aesthetic preferences,” writes art historian Debra Hassig in RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics. Hassig cites the example of the twelfth or thirteenth-century Ashmole Bestiary, where humorous images include a big lion cowering in terror at a rooster. The text alongside relates this supposed cowardly attribute of the lion; the image conveys it without language through the anthropomorphic facial expressions of the two creatures.

Lions were also prevalent on medieval door knockers, where they were represented as stern guardians. They regularly appeared on the heraldry of European royalty, their predatory poses symbolizing authority and a noble independence. Researcher Anita Glass in Gesta considers a bronze lion with a mane of scroll-like curls, its body almost ornamental in its curves. “The unknown artist who cast it was not essentially interested in the physical appearance and proportions of a real animal, but in what the animal expressed,” Glass writes. “The large globular head, the heavy blocklike paws and the twisted body tell us that a lion is powerful and ferocious.”

There was likely some hearsay involved in the imperfect medieval lions, yet the artists were often breaking with nature to express an idea. Rather than mistakes, these #notalion specimens can be viewed as artistic decisions, albeit ones which appear delightfully strange to our modern eyes.

On the popular Twitter hashtag #notalion, medieval historians and aficionados share the most un-leonine lions from the Middle Ages. One on the edge of an illuminated manuscript smiles gently, its flat face almost human; another from the eleventh century seems to smirk with pride at the glory of his mane that radiates like the sun.

Why do these lions look, well, not like lions? Scholar Constantine Uhde wrote for The Workshop in 1872 that in early Christian and Romanesque sculpture, “the physiognomy of the lion gradually loses more and more of its animal aspect, and tends, though quaintly, to the human.” The obvious explanation is that there weren’t that many lions in medieval Europe to model for artists, and the accessible representations for copying had the same lack of realism.

As art historian Charles D. Cuttler writes in Artibus et Historiae, however, there actually were a number of lions on the continent, imported from Africa and Asia: “There are many accounts of their presence and even their breeding, first at various courts and then in the cities; they were kept in Rome by the popes as early as 1100, and Villard de Honnecourt made a drawing of a lion ‘al vif’ [‘from life’] in the thirteenth century—where he saw the animal is unknown.”

The city of Florence had lions in the thirteenth century; lions were at Ghent’s court in the fifteenth century; and a lion house was built at the court of the Counts of Holland sometime after 1344, so it’s not impossible that first-hand accounts of lions were available to artists.

The inaccuracy of medieval lions may have been a stylistic preference, particularly in a bestiary, or compendium of beasts. “Because the artists chose to illustrate the animals rather than their accompanying moralizations, they had more freedom of choice in their imagery: the bestiaries provided them with more latitude for the expression of design and other aesthetic preferences,” writes art historian Debra Hassig in RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics. Hassig cites the example of the twelfth or thirteenth-century Ashmole Bestiary, where humorous images include a big lion cowering in terror at a rooster. The text alongside relates this supposed cowardly attribute of the lion; the image conveys it without language through the anthropomorphic facial expressions of the two creatures.

Lions were also prevalent on medieval door knockers, where they were represented as stern guardians. They regularly appeared on the heraldry of European royalty, their predatory poses symbolizing authority and a noble independence. Researcher Anita Glass in Gesta considers a bronze lion with a mane of scroll-like curls, its body almost ornamental in its curves. “The unknown artist who cast it was not essentially interested in the physical appearance and proportions of a real animal, but in what the animal expressed,” Glass writes. “The large globular head, the heavy blocklike paws and the twisted body tell us that a lion is powerful and ferocious.”

There was likely some hearsay involved in the imperfect medieval lions, yet the artists were often breaking with nature to express an idea. Rather than mistakes, these #notalion specimens can be viewed as artistic decisions, albeit ones which appear delightfully strange to our modern eyes.