Other than the issue that this seems like a real stupid idea... isn't this a real stupid idea? Lagrangian points are cool and awesome and we exploit them, but they aren't magic and are unstable (for objects in it). HOw is dust supposed to stay within it. I can't imagine it'd take much for either it to be destabilized by the Earth, Sun, Jupiter, a passing by duck, or to settle on a nearby small rock also sharing space in the Lagrangian spot.

And this assumes it stops there.

I'll let a scientist here tell me I'm wrong, but it just sounds real dumb.

Well, you could just read the quoted part of the abstract, which very clearly sets out that the plan is NOT to use L1, but instead to launch it "on ballistic trajectories that cross near the Earth-Sun line of sight. We have identified orbits that allow dust grains to provide shade for days, almost as long as for dust deployed near L1, the Earth-Sun Lagrange point".

The paper appears to be suggesting that earlier proposals for a sun shield at L1 would produce sub-optimal results, in comparison to a new plan of simply feeding a continuous stream of material into less stable orbits.

This also provides the benefit of being rapidly adjustable (by simply turning off the launchers) in the event that less cooling is required for any reason.

In summary, you're not wrong that it's real dumb to try to put dust at L1; but you are wrong to imagine that you disagree with the authors of the paper on that point.

Either way, the placing of dust or other shielding to reduce insolation would be a half-measure. These kinds of solutions are a way to address temperature rise due to excess CO

2, but do nothing to mitigate other problems that it causes, such as ocean acidification.

The optimum solution is to reduce atmospheric CO

2 concentrations to pre-industrial levels. This can be achieved by decreasing the amount of new CO

2 we put into the atmosphere, or by increasing the amount of CO

2 we remove from the atmosphere for geological timescales.

The first part is straightforward enough; We just need to burn less fossil fuel. But it's like losing weight by eating less food - it only works if you

actually burn less fossil fuel. Hiding the fossil fuel burning behind intermittent generation of low emissions power is like refusing to eat your dinner in order to lose weight, but then sneaking a donut after everyone has gone to bed.

The atmosphere, like your waistline, doesn't respond to propaganda, or to public displays of virtue; It responds to what actually happens in aggregate over the long term.

Nobody cares how much of your dinner you left on your plate, or how many wind turbines or solar panels you installed. All that matters is the total amount of food you eat from all sources over the long term, or the total net amount of CO

2 you emitted, from the aggregate of all activities.

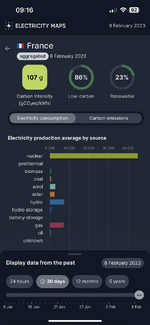

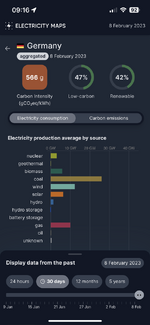

There's no mystery here. We can see what electricity generation strategies are effective against CO

2 emissions, and which are not. The countries with effective strategies are consistently coloured green on the maps I posted above, and the ones whose strategies are less effective are yellow, brown, or (for the least effective ones) black.

It's easy to see that investing in hydroelectric and nuclear power gets good results; Investing in gas as an alternative to coal gets poor results (but is better than nothing); and that investing in wind and solar gets good initial results, but that the return on further investment in these technologies drops off dramatically as they reach ~30% of supply.

That really should not be a surprise, because these technologies only operate about 30% of the time.