As Grant explains: “This new graph maps the ideologies of 44 different religious groups using data comes from Pew’s Religious Landscape survey. This survey included 32,000 respondents. It asked very specific questions on religion that allow us to find out the precise denomination, church, or religion of each person.”

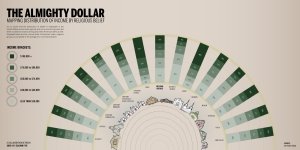

In other words, the dimensions of each color-coded circle reflect the relative size of the religious group it represents, and a circle’s position on the graph illustrates how the faithful feel about the government’s involvement in both the economy (bigger government with more services vs. smaller government with less services) and morality (greater protection of morality vs. less protection of morality). While the chart is revealing on its own, the policy questions in play — the economy and morality — are perhaps best analyzed alongside data detailing the average income of religious people from different faith groups. Pew Research has information on just that, which was used by GOOD magazine and Column Five in 2010 to create this beautiful infographic:

At first glance, one of the most notable correlations between the two charts is how closely racial and economic trends track with the demographics of religious groups — particularly on the question of government services. Since churches often serve as community hubs, pastors and congregants — and, by extension, full denominations — are usually sensitive to issues faced by people in their pews. Historically black Protestant denominations, for instance, are shown as having a high percentage of congregants (roughly 47 percent) who make less than $30,000 a year. This income bracket disproportionally benefits from crucial social programs such as the Affordable Care Act and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (a.k.a., food stamps), so it makes sense that denominations such as National and unaffiliated Baptists show up as overwhelmingly in favor of a government that offers more services. Similarly, White Mainline Protestants such as the United Methodist Church, the Episcopal church, and the Presbyterian Church (USA) have some of the wealthiest congregants in the country (36 percent of White Mainliners make over $75,000 a year) who don’t usually come in contact with many social services. As such, it’s not entirely surprising that they skew towards the “smaller government, less services” section of Grant’s scale. Meanwhile, Catholics, whose numbers include a relatively even distribution of income brackets that closely matches the national average, are situated roughly in the center of the chart.

But while income seems to indicate the probable political positions of some faith groups on the graph, Grant’s compilation also highlights several notable — and politically perplexing — exceptions. Sixty-five percent of Hindus make over $75,000 a year, for instance, but Grant’s chart depicts this wealthy group as firmly endorsing big government. Conversely, 58 percent of evangelicals — who, in Pew’s designation, are overwhelmingly white — make less than $50,000 a year, and many benefit directly from social services: white non-Hispanics make up 42 percent of our nation’s poor and receive 69 percent of government benefits, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Yet most of the evangelical denominations, marked in dark blue, are huddled near the upper right side of Grant’s graph, indicating a solid preference for a smaller government with less services.

There are also odd outliers, such as white Pentecostals — who, on average, are poorer and less educated than the average American. They, like historically black churches, show up as decidedly left-of-center on the big government question, breaking the trend set by their fellow white conservative Christians.

Interestingly, the economic divide is also arguably even more consistent on the question of whether or not the federal government should do more to protect morality. One could contend, for example, that Grant’s graph adds weight to studies positing that wealthier people tend to gravitate towards looser moral standards. As mentioned, historically black churches and conservative evangelical denominations both have high percentages of churchgoers who earn less money than the national average, and both groups sit almost entirely on the half of the graph that calls for a greater protection of morality. But groups with high income rates — Buddhists, Unitarians, non-conservative Jews, the religiously unaffiliated (listed here as “nothing in particular”), and Mainline protestants — all lean towards a hypothetical administration that does less to reinforce moral codes. But this “the rich hate morals” argument gets muddled pretty quickly: Mainline protestant denominations are relatively wealthy, but they are decidedly more liberal than evangelicals on social issues such as homosexuality. As such, it’s possible that these progressively-minded respondents conflate the idea of “protecting morality” with harmful policies that restrict the rights of LGBT people.

The notable outlier on the morality question is the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (LDS), or Mormons, who live pretty comfortably as a people yet fervently support a more morally-minded administration. There are a number of possible explanations for this, but one could be that the top-down style of the LDS church and its teachings simply have an unusually deep impact the lives of Mormons. Three scholars actually explored this phenomenon a new book about the church, highlighting how Mormons are now one of the most “politically cohesive” groups in the country. This “theological impact” argument could also explain another odd division within the Jewish community that shows up in Grant’s chart: Adherents to Judaism fair relatively well economically across the board, but Conservative and Orthodox Jews seem to prefer a government that does more to protect morality. More liberal Jews, on the other hand, deeply support leadership that does less to protect moral standards.

Grants graph also exposes some possible disconnects between the professed beliefs of religious institutions and the opinions of those in their pews. For example, according to the chart, virtually all Mainline protestant denominations are firmly situated in the “smaller government, less services” side of the ideological spectrum. Yet Mainline protestant denominational heads have repeatedly and passionately participated in efforts such as the “Circle of Protection,” an ecumenical effort to safeguard social services that help poorer Americans. The same is true for Catholics: Catholic leaders have lobbied fiercely for both social programs (such as food stamps) and against policies they see as morally abhorrent (such as contraception), yet Pew’s data and Grant’s chart shows the average Catholic as roughly at the center of the idealogical spectrum on these questions.