SimpleDon

Veteran Member

Marx was right - at least about somethings.

We have another anniversary to celebrate tomorrow and it is a really big one, the 200th anniversary of Karl Marx's birth.

This article from The Economist offers some advice to the Rulers of the world: read Karl Marx! or Second time, farce.

The article presents Marx as a flawed genius, who had some valuable insights into capitalism but who turned these nuggets of truth into a philosophy that the "40% of humanity who lived under Marxist regimes for much of the 20th century endured famines, gulags and party dictatorships." And then asks the obvious question "Why does the world remain fixated on the ideas of a man who helped to produce so much suffering?" To which they answer, "The obvious reason is the sheer power of those ideas" and "His ideas were as much religious as scientific—you might even call them religion repackaged for a secular age." That

Of course, Marx got most things wrong in his philosophy.

I do agree with this. In fact. I realized that the economists from whom I have gained the most were either raised under Communism or were socialists and either converted to capitalism or just made astute commentary about it, unfortunately few will reconize these names; Michał Kalecki (better than Keynes about Keynesian economics),

Michał Kalecki (better than Keynes about Keynesian economics),  Piero Sraffa (the Cambridge Capital Controversy),

Piero Sraffa (the Cambridge Capital Controversy),  Nicholas Kaldor (the founder of post-Keynesian economics), and

Nicholas Kaldor (the founder of post-Keynesian economics), and  Karl Polanyi (who explained the roots of neoliberalism). There is something to be said for being on the outside looking in to see something that others are too close to to see. This certainly applies to Marx who first described the impact of class in capitalism.

Karl Polanyi (who explained the roots of neoliberalism). There is something to be said for being on the outside looking in to see something that others are too close to to see. This certainly applies to Marx who first described the impact of class in capitalism.

So the questions I ask are:

Do you accept that Marx got somethings right about capitalism even though his body of work taken as a whole caused immense suffering to millions of people for a century?

Or do you require the authors you look to to be right about most of their assertions before you credit any of their assertions?

Can you give examples of those in economics, that have shaped your outlook? I promise not to list the incorrect ideas that they had. This isn't a set up.

If you do credit Marx with some correct insights into the problems with capitalism, what are they?

We have another anniversary to celebrate tomorrow and it is a really big one, the 200th anniversary of Karl Marx's birth.

This article from The Economist offers some advice to the Rulers of the world: read Karl Marx! or Second time, farce.

The article presents Marx as a flawed genius, who had some valuable insights into capitalism but who turned these nuggets of truth into a philosophy that the "40% of humanity who lived under Marxist regimes for much of the 20th century endured famines, gulags and party dictatorships." And then asks the obvious question "Why does the world remain fixated on the ideas of a man who helped to produce so much suffering?" To which they answer, "The obvious reason is the sheer power of those ideas" and "His ideas were as much religious as scientific—you might even call them religion repackaged for a secular age." That

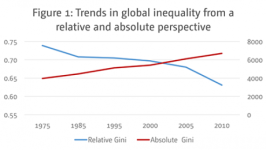

the continuing interest in Marx, however, is that his ideas are more relevant than they have been for decades. The post-war consensus that shifted power from capital to labour and produced a “great compression” in living standards is fading. Globalisation and the rise of a virtual economy are producing a version of capitalism that once more seems to be out of control. The backwards flow of power from labour to capital is finally beginning to produce a popular—and often populist—reaction. No wonder the most successful economics book of recent years, Thomas Piketty’s “Capital in the Twenty-First Century”, echoes the title of Marx’s most important work and his preoccupation with inequality.

The prophet of Davos

Marx argued that capitalism is, in essence, a system of rent-seeking: rather than creating wealth from nothing, as they like to imagine, capitalists are in the business of expropriating the wealth of others. Marx was wrong about capitalism in the raw: great entrepreneurs do amass fortunes by dreaming up new products or new ways of organising production. But he had a point about capitalism in its bureaucratic form. A depressing number of today’s bosses are corporate bureaucrats rather than wealth-creators, who use convenient formulae to make sure their salaries go ever upwards. They work hand in glove with a growing crowd of other rent-seekers, such as management consultants (who dream up new excuses for rent-seeking), professional board members (who get where they are by not rocking the boat) and retired politicians (who spend their twilight years sponging off firms they once regulated).

Capitalism, Marx maintained, is by its nature a global system: “It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connections everywhere.” That is as true today as it was in the Victorian era. The two most striking developments of the past 30 years are the progressive dismantling of barriers to the free movement of the factors of production—goods, capital and to some extent people—and the rise of the emerging world. Global firms plant their flags wherever it is most convenient. Borderless CEOs shuttle from one country to another in pursuit of efficiencies. The World Economic Forum’s annual jamboree in Davos, Switzerland, might well be retitled “Marx was right”.

Of course, Marx got most things wrong in his philosophy.

Marx’s greatest failure, however, was that he underestimated the power of reform—the ability of people to solve the evident problems of capitalism through rational discussion and compromise. He believed history was a chariot thundering to a predetermined end and that the best that the charioteers can do is hang on. Liberal reformers, including his near contemporary William Gladstone, have repeatedly proved him wrong. They have not only saved capitalism from itself by introducing far-reaching reforms but have done so through the power of persuasion. The “superstructure” has triumphed over the “base”, “parliamentary cretinism” over the “dictatorship of the proletariat”.

Nothing but their chains

The great theme of history in the advanced world since Marx’s death has been reform rather than revolution. Enlightened politicians extended the franchise so working-class people had a stake in the political system. They renewed the regulatory system so that great economic concentrations were broken up or regulated. They reformed economic management so economic cycles could be smoothed and panics contained. The only countries where Marx’s ideas took hold were backward autocracies such as Russia and China.

Today’s great question is whether those achievements can be repeated. The backlash against capitalism is mounting—if more often in the form of populist anger than of proletarian solidarity. So far liberal reformers are proving sadly inferior to their predecessors in terms of both their grasp of the crisis and their ability to generate solutions. They should use the 200th anniversary of Marx’s birth to reacquaint themselves with the great man—not only to understand the serious faults that he brilliantly identified in the system, but to remind themselves of the disaster that awaits if they fail to confront them.

I do agree with this. In fact. I realized that the economists from whom I have gained the most were either raised under Communism or were socialists and either converted to capitalism or just made astute commentary about it, unfortunately few will reconize these names;

So the questions I ask are:

Do you accept that Marx got somethings right about capitalism even though his body of work taken as a whole caused immense suffering to millions of people for a century?

Or do you require the authors you look to to be right about most of their assertions before you credit any of their assertions?

Can you give examples of those in economics, that have shaped your outlook? I promise not to list the incorrect ideas that they had. This isn't a set up.

If you do credit Marx with some correct insights into the problems with capitalism, what are they?