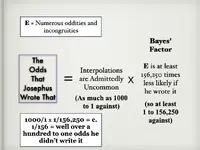

Sound methodology requires (1) that we attend to the effect of our unevidenced assumptions on the probability of our theory; (2) that we attend to how likely our theory makes all the evidence (including what isn’t in evidence, not just what is); and (3) that we compare our theory’s merits in these regards to any other viable theory, especially the most viable competing theory you can find or contrive.

Here is the text in Greek (which I extracted from the industry’s digital standard, the

TLG):

(199) ὁ δὲ νεώτερος Ἄνανος, ὃν τὴν ἀρχιερωσύνην ἔφαμεν εἰληφέναι, θρασὺς ἦν τὸν τρόπον καὶ τολμητὴς διαφερόντως, αἵρεσιν δὲ μετῄει τὴν Σαδδουκαίων, οἵπερ εἰσὶ περὶ τὰς κρίσεις ὠμοὶ παρὰ πάντας τοὺς Ἰουδαίους, καθὼς ἤδη δεδηλώκαμεν. (200) ἅτε δὴ οὖν τοιοῦτος ὢν ὁ Ἄνανος, νομίσας ἔχειν καιρὸν ἐπιτήδειον διὰ τὸ τεθνάναι μὲν Φῆστον, Ἀλβῖνον δ’ ἔτι κατὰ τὴν ὁδὸν ὑπάρχειν, καθίζει συνέδριον κριτῶν καὶ παραγαγὼν εἰς αὐτὸ τὸν ἀδελφὸν Ἰησοῦ τοῦ λεγομένου Χριστοῦ, Ἰάκωβος ὄνομα αὐτῷ, καί τινας ἑτέρους, ὡς παρανομησάντων κατηγορίαν ποιησάμενος (201) παρέδωκε λευσθησομένους. ὅσοι δὲ ἐδόκουν ἐπιεικέστατοι τῶν κατὰ τὴν πόλιν εἶναι καὶ περὶ τοὺς νόμους ἀκριβεῖς βαρέως ἤνεγκαν ἐπὶ τούτῳ καὶ πέμπουσιν πρὸς τὸν βασιλέα κρύφα παρακαλοῦντες αὐτὸν ἐπιστεῖλαι τῷ Ἀνάνῳ μηκέτι τοιαῦτα πράσσειν· μηδὲ γὰρ τὸ (202) πρῶτον ὀρθῶς αὐτὸν πεποιηκέναι. τινὲς δ’ αὐτῶν καὶ τὸν Ἀλβῖνον ὑπαντιάζουσιν ἀπὸ τῆς Ἀλεξανδρείας ὁδοιποροῦντα καὶ διδάσκουσιν, ὡς οὐκ ἐξὸν ἦν Ἀνάνῳ χωρὶς τῆς ἐκείνου γνώμης καθίσαι συνέδριον. (203) Ἀλβῖνος δὲ πεισθεὶς τοῖς λεγομένοις γράφει μετ’ ὀργῆς τῷ Ἀνάνῳ λήψεσθαι παρ’ αὐτοῦ δίκας ἀπειλῶν. καὶ ὁ βασιλεὺς Ἀγρίππας διὰ τοῦτο τὴν Ἀρχιερωσύνην ἀφελόμενος αὐτὸν ἄρξαντα μῆνας τρεῖς Ἰησοῦν τὸν τοῦ Δαμναίου κατέστησεν.

The old Whiston translation

renders this as (emphasis mine):

[The] younger Ananus, who, as we have told you already, took the high priesthood, was a bold man in his temper, and very insolent; he was also of the sect of the Sadducees, who are very rigid in judging offenders, above all the rest of the Jews, as we have already observed; when, therefore, Ananus was of this disposition, he thought he had now a proper opportunity. [The Roman prefect] Festus was now dead, and Albinus [his replacement] was but upon the road; so [Ananus] assembled the Sanhedrin of judges, and brought before them the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ, whose name was James, and some others; and when he had formed an accusation against them as breakers of the law, he delivered them to be stoned: but as for those who seemed the most equitable of the citizens, and such as were the most uneasy at the breach of the laws, they disliked what was done; they also sent to the king [Agrippa], desiring him to send to Ananus that he should act so no more, for that what he had already done was not to be justified; nay, some of them went also to meet Albinus, as he was upon his journey from Alexandria, and informed him that it was not lawful for Ananus to assemble a Sanhedrin without his consent. Whereupon Albinus complied with what they said, and wrote in anger to Ananus, and threatened that he would bring him to punishment for what he had done; on which king Agrippa took the high priesthood from him, when he had ruled but three months, and made Jesus, the son of Damneus, High Priest.

MacDonald’s theory requires: that James the brother of Jesus Christ taught the abolition of Torah law or some radical set of changes to it; that Ananus cared so much about that as to have him illegally executed; and that the rest of the Jewish elite were not supportive of that but in fact outraged by it and

punished Ananus for it. Already little of this makes logical sense. The Jewish elite persecuted Christians; they didn’t persecute their persecutors. And the only prominent James we know about was part of the

pro-Torah faction of Christians, not the Pauline faction who argued for abandoning strict Torah observance. There is no evidence whatever that this (or indeed any) James was teaching radical deviations from Torah law. All evidence we do have suggests he would have been

against the Christian factions who did that.

So right from the start, MacDonald’s hypothesis requires inventing

ad hoc suppositions, nowhere in evidence, that this brother of Jesus had taken or switched sides with the anti-Torah Pauline sect, and was advocating it so ardently in Judea that the Sanhedrin stoned him for it—an event nowhere recorded, not even in the book of Acts, which mentions no James the brother of Jesus at all, and which only mentions the known Torah-faction James

being beheaded, not stoned, and by King Agrippa, not the Sanhedrin (much less Ananus), nor for this reason, and this action being

approved by the elite, rather than (as Josephus’s story has it), so ardently opposed by the Jewish elite as to result in Royal and Roman intervention in deposing a High Priest who instigated the murder.

So MacDonald’s theory of this passage requires improbable supposition after improbable supposition even before we get to testing it against the evidence for it.

--Carrier (27 December 2020).

""What Did Josephus Mean by That?" A Case Study in the Relationship between Evidence and Probability".

Richard Carrier Blogs.