lpetrich

Contributor

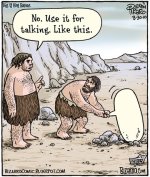

Human language is far in advance of what every other present-day species has, with the possible exception of what dolphins may have. Efforts to teach sign language to chimpanzees has resulted in the animals learning lots of signs, but very little beyond that. They can make some two-sign combinations, but that is about it.

Various biologists and linguists have developed a sizable number of theories about its origin, and some of them have given these theories whimsical names. Here's what I've found:

Sources:

Origin of language

Origin of language

The Origins of Language - C. George Boeree

Historical Linguistics (PowerPoint)

Linguistic Hypotheses on the Origins of Language | Free Language

The Origin of Language (MSWord)

The Origin of Language : Sturtevant, E. H. : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive

The Evolution of Language

Various biologists and linguists have developed a sizable number of theories about its origin, and some of them have given these theories whimsical names. Here's what I've found:

- ma-ma -- attaching the easiest syllables to significant objects (?)

- ta-ta -- imitation of body movements like gestures (Sir Richard Paget 1930)

- bow-wow -- imitation of sounds (?, Max Müller 1861)

- pooh-pooh -- interjections, instinctive emotive cries (?, Max Müller 1861)

- ding-dong -- sounds and meanings corresponding, like sound symbolism (?, Max Müller 1861)

- yo-he-ho -- rhythmic chants, like when coordinating efforts in heavy work (?, Max Müller 1861)

- la-la, sing-song -- pleasant audio doodling (Otto Jespersen 1921)

- hey-you -- assertion of identity and calling to others (Géza Révész 1956)

- uh-oh -- warnings (?)

- hocus-pocus -- magical / religious acts (C. George Boeree)

- eureka -- consciously invented (?)

- watch-the-birdie -- lying (Edgar A. Sturtevant 1922)

- pop -- language popped into existence as an evolutionary byproduct (Stephen Jay Gould)

Sources:

The Origins of Language - C. George Boeree

Historical Linguistics (PowerPoint)

Linguistic Hypotheses on the Origins of Language | Free Language

The Origin of Language (MSWord)

The Origin of Language : Sturtevant, E. H. : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive

The Evolution of Language