Looks like the long term dimming may have been due to the instruments being used and not the star itself:

Quote;

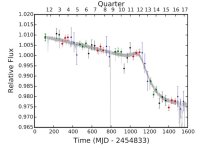

''Now, however, researchers suggest this seemingly century-long dimming trend might not be real. Instead, the apparent darkening may just be due to how astronomical instruments have changed over time.

In the new study, scientists pored over DASCH (Digital Access to a Sky Century @ Harvard) data. This is a collection of more than 500,000 photographic glass plates taken by astronomers at Harvard in Massachusetts between 1885 and 1993 that the university is digitizing.

"It is exciting that we have these century-old data, which are incredibly valuable for checks like this," study lead author Michael Hippke, an amateur astronomer from the German town of Neukirchen-Vluyn, told Space.com.

''The researchers looked not only at Tabby's Star, but also at a number of comparable stars in the DASCH database. Results showed that many of these other stars experienced a drop in brightness similar to that of Tabby's Star in the 1960s.

"That indicates the drops were caused by changes in the instrumentation, not by changes in the stars' brightness," study co-author Keivan Stassun at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, said in a statement.''