Underseer

Contributor

We hear so much about research being done on atheists and atheism that it never occurred to me that it might be a taboo subject in some of the disciplines that can answer some of these questions.

I don't see the point the dizzy valley girl in the video is, like, trying to make, although she seems very excited.

Atheism is specifically studied in sociological studies. Psychologists have endeavored to study belief and disbelief. In any case, Google Scholar returns many studies with the keywords atheist, atheists and disbelief. In my experience, psychologists tend not to be in general high on conservative faith, although they tend to hide it.

She mentions she received no training on how to work with atheists but instead a lot of how to work with religionists. It must be a fad in the US, because psychology has always tended to be extremely secular and most big names of it have been downright atheistic. Say, Rogers, Skinner, Perls, Ellis, Freud himself. In fact if you skim through a psychotherapy manual, the strategies seems pricisely customized for disbelievers and/or viewing things from a realistic, non-mythological point of view. Jung is a notorious exception, having thus a large following from religionists, especially those with New Age leanings.

And, now that I'm talking about traditional psychology, this situation reminds me of figure-ground phenomena. Atheism is big in psychology, but it's completely background. So much that it inspires a large amount of distrust from the more conservative clergy... and I must say, their instincts serve them well.

When i worked on the Suicide Hotline, we had training on how to deal with people who were having problems with their religion.She mentions she received no training on how to work with atheists but instead a lot of how to work with religionists.

When i worked on the Suicide Hotline, we had training on how to deal with people who were having problems with their religion.She mentions she received no training on how to work with atheists but instead a lot of how to work with religionists.

When the authorities say 'gay is evil,' for example and the caller, well, took it personally.

Or if their religious authorities were calling something they'd done an unforgivable sin.

Or if their spouse was abusive but they weren't allowed to divorce.

I just never questioned that this never applied to the atheists that called the hotline.

But how could it?

"Maybe you could shift to a different sect of atheism? You could still not believe in a deity, but maybe you'd be more comfortable not dealing with Odin than not dealing with Jehovah?"

"Well, i'm sorry your atheist authority figure's a shithead. Have you maybe thought about asking the abyss directly if it could ignore you more than it ignored you before?"

"You know, the reformed atheists are more welcoming to a questioning attitude than the orthodox, maybe you could visit one of their non-meeting places?"

Well, yeah, but i was saying it's hard to really anticipate what any given 'grouping' of atheists is going to think about any subject. it's just too informal and individual to make very many useful generalizations. As opposed to groups like Mormons who you can often recognize on sight...Yeah, studying atheism as it relates to mental disorders and clinical psych makes less sense. But it does make sense to study it as a part of and predictor of non-clinical "normal" thought and action.

Well, yeah, but i was saying it's hard to really anticipate what any given 'grouping' of atheists is going to think about any subject. it's just too informal and individual to make very many useful generalizations. As opposed to groups like Mormons who you can often recognize on sight...Yeah, studying atheism as it relates to mental disorders and clinical psych makes less sense. But it does make sense to study it as a part of and predictor of non-clinical "normal" thought and action.

Well, yeah, but i was saying it's hard to really anticipate what any given 'grouping' of atheists is going to think about any subject. it's just too informal and individual to make very many useful generalizations. As opposed to groups like Mormons who you can often recognize on sight...

To a degree, but I bet in many ways Atheists are more coherent than groups like "Christians", "Catholics", "Jews", "Protestants", etc..

Given the small % of open self-labeled "atheists", there can't be too many paths that lead there or there would be more of them.

Psychologists and psychiatrists need to learn how to deal with many forms of mental illness, including (but not limited to) religion.

Obviously they don't spend a huge amount of time explicitly learning how to deal with people who are not depressed; or not psychotic; or not religious.

Motor mechanics don;t learn how to deal with cars that don't have problems with their timing belts either. Not because cars without timing belt problems don't turn up at the garage; but because it is more useful to think in terms of the problem the car does have, rather than the absence of a problem it does not have.

I doubt they're 'coherent' as i understand the term.Atheists are more coherent than groups like "Christians", "Catholics", "Jews", "Protestants", etc..

I doubt they're 'coherent' as i understand the term.Atheists are more coherent than groups like "Christians", "Catholics", "Jews", "Protestants", etc..

Maybe more 'consistent,' if i understand your post.

This is very true, but political/social organizational coherence is separate from coherence of beliefs, ideas, values, etc..But we tend not to organize well. We don't share authoritarian leaders.

If nothing else, because far too many atheists will reject sweeping statements just because they want to be on record that they reject sweeping statements.

Psychologists and psychiatrists need to learn how to deal with many forms of mental illness, including (but not limited to) religion.

Obviously they don't spend a huge amount of time explicitly learning how to deal with people who are not depressed; or not psychotic; or not religious.

Motor mechanics don;t learn how to deal with cars that don't have problems with their timing belts either. Not because cars without timing belt problems don't turn up at the garage; but because it is more useful to think in terms of the problem the car does have, rather than the absence of a problem it does not have.

When I was in school the main reason people went into psychology was they had problems. Unfortunately out of that cohort most haven't really understood themselves. I'm talking about the touchy feelie segment, about 70% of all psychologists, of the other thirty percent about half are in advertising or education and a large part of the remainder are dealing with drugs, cars and airplanes. Needless to say there isn't much money in the study of atheism.

When I was in school the main reason people went into psychology was they had problems. Unfortunately out of that cohort most haven't really understood themselves. I'm talking about the touchy feelie segment, about 70% of all psychologists, of the other thirty percent about half are in advertising or education and a large part of the remainder are dealing with drugs, cars and airplanes. Needless to say there isn't much money in the study of atheism.

Your comments suggest you are referring to "Clinical" Psychologists" / Therapists who deal with "abnormal" or disfunctional thought and behavior.

You are right that people with their own psychological problems are drawn to this field.

However, Clincial Psychologists comprise only 50% of the people who get Ph.D.s in psychology, with the rest being "Experimental" psychologists of which the sub-disciplines are Cognitive, Social, Developmental, Biological, and Educational Psychology. They study normal everyday human learning, thought, emotion, action, and brain function.

90% of undergrads who think they are interested in psychology are interested in Clinical and therapy, but few of these make it to grad school. At the grad school and Ph.D levels there is about an even split between Clinical programs and Experimental programs. BTW, the "experimental" refers to the fact that there focus and training is upon conducting empirical experiments to test hypotheses and theories, mostly about the normal and fundamental aspects of human (and non-human for some bio-psych) psychology. This is the more scientifically grounded side of psychology (sadly many Therapists are borderline scientically illiterate). They are the people who splintered off from the Clinical dominated APA 27 years ago because it was too political, ideological and unscientific to form the APS (Association for Psychological Science). Some abnormal and disfunctional psychology is included in this, but it about conducting controlled experiments.

Most experimental psychologist are drawn to the field for the similar intellectual curiosity that people are drawn to other scientific fields. Atheism and its causes and effects would be something most effectively studied non these non-clinicial experimental psychologists.

Your comments suggest you are referring to "Clinical" Psychologists" / Therapists who deal with "abnormal" or disfunctional thought and behavior.

You are right that people with their own psychological problems are drawn to this field.

However, Clincial Psychologists comprise only 50% of the people who get Ph.D.s in psychology, with the rest being "Experimental" psychologists of which the sub-disciplines are Cognitive, Social, Developmental, Biological, and Educational Psychology. They study normal everyday human learning, thought, emotion, action, and brain function.

90% of undergrads who think they are interested in psychology are interested in Clinical and therapy, but few of these make it to grad school. At the grad school and Ph.D levels there is about an even split between Clinical programs and Experimental programs. BTW, the "experimental" refers to the fact that there focus and training is upon conducting empirical experiments to test hypotheses and theories, mostly about the normal and fundamental aspects of human (and non-human for some bio-psych) psychology. This is the more scientifically grounded side of psychology (sadly many Therapists are borderline scientically illiterate). They are the people who splintered off from the Clinical dominated APA 27 years ago because it was too political, ideological and unscientific to form the APS (Association for Psychological Science). Some abnormal and disfunctional psychology is included in this, but it about conducting controlled experiments.

Most experimental psychologist are drawn to the field for the similar intellectual curiosity that people are drawn to other scientific fields. Atheism and its causes and effects would be something most effectively studied non these non-clinicial experimental psychologists.

Your description of of those in experimental psychology miss me, a person with a PhD in experimental psychology almost completely. My specializations are motivation and emotion, learning, human engineering, psychophysics, and biological (publications in memory, learning, behavior genetics, and neuronal chemical characterization). I also have publications in psychometics.

Correct, but how many graduate Ph.D programs in Psychology do most major Universities have? About 4-6 typically corresponding to the subdivisions I mentioned. Of those 56 "divisions" there are less than 10 that correspond to any actual graduate program, and they are the broader categories corresponding closely to the one's I listed. For example, one of those "divisions' is "International Psychology". That is not an area or topic of study within psychology. Other divisions are specific to a very narrow topic for which you cannot get a doctorate, but which is just one of many things one studies within a broader sub-field, such the APA division of "Trauma Psychology" which is just a topic within Clinical Psychology, and nearly all the psychologist in the "Trauma" division of APA got their doctorate from a Clinical Psychology graduate program, as is the case for most of those 56 "divisions".I just checked and the number of divisions in APA is 56 http://www.apa.org/about/division/index.aspx

I agree that many clinical psychologists who author studies on their own in clinical psychology journals are probably not that up to it. However those who really try do so usually under the guidance of both experimental psychologists and clinical psychiatrists and these studies are usually first rate.

APS has 26 k members and APA has 137k members.

There are quality clinical psychology journals that publish sound research, mostly by academic clinical researchers who are not practicing therapists. The problem is that most therapists do not actually read or apply that sound science in their practice, plus the mountain of pseudo-science journals that cater to the therapy and counseling community.

I don't see the point the dizzy valley girl in the video is, like, trying to make, although she seems very excited.

Atheism is specifically studied in sociological studies. Psychologists have endeavored to study belief and disbelief. In any case, Google Scholar returns many studies with the keywords atheist, atheists and disbelief. In my experience, psychologists tend not to be in general high on conservative faith, although they tend to hide it.

She mentions she received no training on how to work with atheists but instead a lot of how to work with religionists. It must be a fad in the US, because psychology has always tended to be extremely secular and most big names of it have been downright atheistic. Say, Rogers, Skinner, Perls, Ellis, Freud himself. In fact if you skim through a psychotherapy manual, the strategies seems pricisely customized for disbelievers and/or viewing things from a realistic, non-mythological point of view. Jung is a notorious exception, having thus a large following from religionists, especially those with New Age leanings.

And, now that I'm talking about traditional psychology, this situation reminds me of figure-ground phenomena. Atheism is big in psychology, but it's completely background. So much that it inspires a large amount of distrust from the more conservative clergy... and I must say, their instincts serve them well.

There are quality clinical psychology journals that publish sound research, mostly by academic clinical researchers who are not practicing therapists. The problem is that most therapists do not actually read or apply that sound science in their practice, plus the mountain of pseudo-science journals that cater to the therapy and counseling community.

Here is the nut. There are many articles publishing ordinal data results using methods designed for interval level data. I never published in any journal that permitted that. All my data was firmly tied to physical data for which there are standards in Paris. All my measurements included zero or a ratio between scales which have a zero. I'm very particular that way.

Sure ordinal stuff is interesting, but, if one can't find a way to tie what one is doing to some physical anchor that is scaled and includes zero its not scientific data. Its whatever and it can't be employed to generate the basis for physical theory which is what a successful psychological theory will be. Calling your stuff psychological does not include a get out of material jail free.

Its the major problem with most psychological data done by those outside the realm where there is a parent suite of material scales upon which one can relate with what one is dealing . It is not permitted for one to invent new relationships and call them scales without connecting them to sound physical bases.

In simple terms ordinal data is not suitable for building physical theory. If I want to measure psychological workload I have to relate it or effort to caloric or physiological measures that can be stated in time and magnitude. I'm sure one, with time and patience construct various mental abilities related to such as rates of oxygen uptake in very particular areas such as ventral lateral frontal cortex which is related to such as arousal, sensory and other attributes that gives one confidence one is working with a particular kind of mental attribute. Very few psychologists even try.

Now why don't psychologists study atheism. Well they do in droves. The problem is the data they consider cannot be held to controlled conditions nor addressed via material references. So Psychologists nor anyone else has ever done a scientific paper on atheism.

I am a psychologist and I learned from many who never published a scientific paper in their careers. Sure they've published at rates up to 10 to 20 papers per year, but none of it will ever be part of any scientific psychological theory. There is some psychological theory that doesn't rewind or recycle every 20 years or so. All of it includes scientific papers meeting the criteria I outlined above.

To tough? Sorry. that's the way things are.

Here is the nut. There are many articles publishing ordinal data results using methods designed for interval level data. I never published in any journal that permitted that. All my data was firmly tied to physical data for which there are standards in Paris. All my measurements included zero or a ratio between scales which have a zero. I'm very particular that way.

Sure ordinal stuff is interesting, but, if one can't find a way to tie what one is doing to some physical anchor that is scaled and includes zero its not scientific data. Its whatever and it can't be employed to generate the basis for physical theory which is what a successful psychological theory will be. Calling your stuff psychological does not include a get out of material jail free.

Its the major problem with most psychological data done by those outside the realm where there is a parent suite of material scales upon which one can relate with what one is dealing . It is not permitted for one to invent new relationships and call them scales without connecting them to sound physical bases.

In simple terms ordinal data is not suitable for building physical theory. If I want to measure psychological workload I have to relate it or effort to caloric or physiological measures that can be stated in time and magnitude. I'm sure one, with time and patience construct various mental abilities related to such as rates of oxygen uptake in very particular areas such as ventral lateral frontal cortex which is related to such as arousal, sensory and other attributes that gives one confidence one is working with a particular kind of mental attribute. Very few psychologists even try.

Now why don't psychologists study atheism. Well they do in droves. The problem is the data they consider cannot be held to controlled conditions nor addressed via material references. So Psychologists nor anyone else has ever done a scientific paper on atheism.

I am a psychologist and I learned from many who never published a scientific paper in their careers. Sure they've published at rates up to 10 to 20 papers per year, but none of it will ever be part of any scientific psychological theory. There is some psychological theory that doesn't rewind or recycle every 20 years or so. All of it includes scientific papers meeting the criteria I outlined above.

To tough? Sorry. that's the way things are.

What you are advancing is extremist methodological physicalism (going well beyond methodological naturalism), which itself is not a scientifically defensible position, and more akin to a dogmatic religion than an intellectually sound philosophy of science. It is a highly contested notion in philosophy of science, and to assert that it is "the way things are" is unscientifically dogmatic.

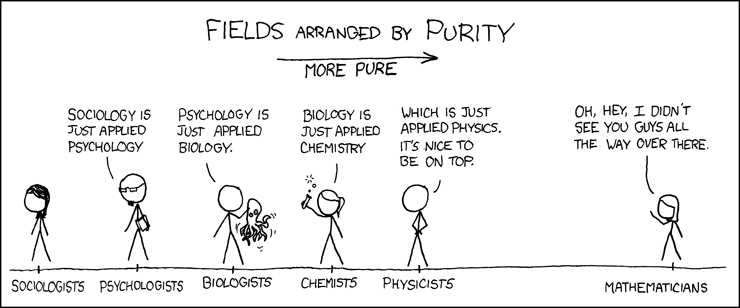

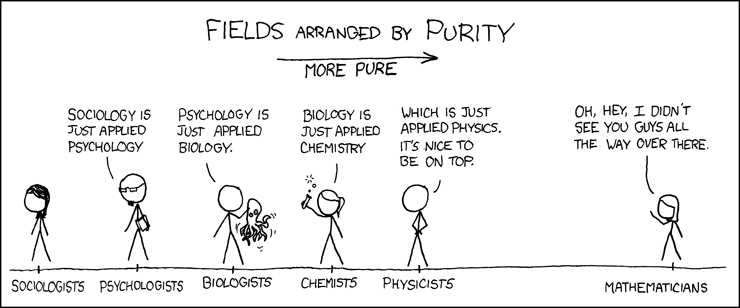

It is the same argument used by some physicist to strip scientific status from chemistry, biology, and all sciences outside of physics (and not all of physics).

In addition, scales with a true zero point, representing the total absence of something are ratio scales, not interval scales. There is nothing resembling a defensible definition of "science" that says all variables must be measured on a ratio scale. Ratio scales are only required for knowing the absolute value of something, not for observing relative variability in the state of something (and covariance among somethings), which is what 99% of science is about.

Third, there is nothing that says that science cannot measure variability in the the observable (and material) manifestations of the underlying material mechanisms, and thus serve as a model of variance and covariance, especially when the observable manifestations are what we actually care about predicting and impacting (such violent behavior, whose variance cannot currently be mapped onto variance in a specific material state). The entire reason why the concept of "operational definition" exists in science is because what and how empirical measurements are made (the operational definition) is only one manifestation of theoretical constructs of interest, and the mapping between the operational definition and the theoretical construct varies both between and within scientific disciplines.

If the events of actual interest, human behavior and subjective mental states could all be measured in terms specific material states, then the work of psychology would be over and they could all go home, because then everything else to be done would physics. Again, your argument presumes that if it isn't physics, it isn't science.

In fact, measurement of the physical brain states in neuroscience is only useful for understanding human thought and behavior because of the the kind of behavioral science you claim is unscientific, but without with no FMRI study could ever say anything about human thought and behavior beyond, gee, there is more blood flow to region X during task A than B. And task A and B would have to be describe in purely numerical terms, since your view rejects all conceptual categories as meaningless, and things only exist in terms of the quantities they represent on ratio variables.

The problematic lack of scientific foundation in much of therapeutic practice is not due to using ordinal rather than ratio scales or failing to directly measure the material system giving rise to thought and behavior. The problem is that many therapeutic practices are based in emotional/ideological preferences of practitioners and lack of any form of systematic observation and measurement and sensitivity to the constraints they impose. It isn't empirically grounded at all, whether you want to call that empirically grounding "science" or some other term.