Mihail Zilbermint is used to treating diabetes — he heads a special team that cares for patients with the metabolic disorder at Suburban Hospital in Bethesda, Md. But as the hospital admitted increasing numbers of patients with covid-19, his caseload ballooned.

“Before, we used to manage maybe 18 patients per day,” he said. Now his team cares for as many as 30 daily.

Many of those patients had no prior history of diabetes. Some who developed elevated blood sugar while they had covid-19, the illness caused by the novel coronavirus, returned to normal by the time they left the hospital. Others went home with a diagnosis of full-blown diabetes. “We’ve definitely seen an uptick in patients who are newly diagnosed,” Zilbermint said.

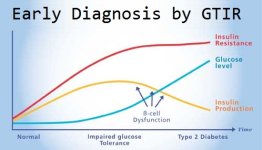

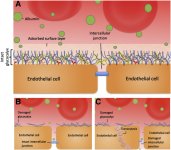

Although covid-19 often attacks the lungs, it is increasingly associated with a range of problems including blood clots, neurological disorders, and kidney and heart damage. Researchers say new-onset diabetes may soon be added to those complications — both Type 1, in which people cannot make the insulin needed to regulate their blood sugar, and Type 2, in which they make too little insulin or become resistant to their insulin, causing their blood sugar levels to rise. But scientists do not know whether covid-19 might hasten already developing problems or actually cause them — or both.

As early as January 2020, doctors in Wuhan, China, noticed elevated blood sugar in patients with covid-19. Physicians in Italy, another early hot spot, wondered whether diabetes diagnoses might follow, given the long-observed association between viral infections and the onset of diabetes. That association was seen in past outbreaks of other coronavirus illnesses such as influenza and SARS.

A year after the pandemic began, the precise nature and scope of the covid-diabetes link remain a mystery. Many of those who develop diabetes during or after covid-19 have risk factors, such as obesity or a family history of the disease. Elevated blood glucose levels also are common among those taking dexamethasone, a steroid that is a front-line treatment for covid-19. But cases also have occurred in patients with no known risk factors or prior health concerns. And some cases develop months after the body has cleared the virus.

John Kunkel, a 47-year-old banking executive in Evening Shade, Ark., was one of the surprise cases. He was hospitalized with covid-19 in early July. During a follow-up visit with his doctor, he learned he had dangerously high blood glucose levels and was readmitted. Kunkel has since received a diagnosis of Type 2 diabetes.

“I had no preexisting health issues,” he said. “I was blown away. Why?”

Kunkel has had five emergency room visits and three hospital stays since getting covid-19. He recently lost his job because he was unable to return to work, given his continuing health problems. “Will you get your life back?” he asked. “Nobody knows.”

As many as 14.4 percent of people hospitalized with severe covid-19 developed diabetes, according to a global analysis published Nov. 27 in the journal Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. The international group of researchers sifted through reports of uncontrolled hyperglycemia, or high blood sugar, in more than 3,700 covid-19 patients across eight studies. While those diagnoses might be the result of a long-observed response to severe illness, or to treatment with steroids, the authors wrote, a direct effect from covid-19 “should also be considered.”

Concerns that covid-19 might be directly implicated also were supported, they said, by the exceptionally high doses of insulin that diabetes patients with severe covid-19 often require and the dangerous complications they develop.

Researchers do not understand exactly how covid-19 might trigger Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes, or whether the cases are temporary or permanent. But they are racing to find answers to these and other questions, including whether the novel coronavirus may have spawned an entirely new type of diabetes that might play out differently from the traditional forms of the disease.

Francesco Rubino, a diabetes surgery professor at King’s College London, is convinced there is an underlying connection between the diseases.

Over the summer, he and a group of other diabetes experts launched a global registry of patients with covid-19-related diabetes. After they spread the word with an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, more than 350 institutions from across the world responded, he said.

New diagnoses of diabetes in people with no classic risk factors also are scattered throughout case reports: A 37-year-old, previously healthy Chinese man who went to the hospital with a severe, and in some cases fatal, diabetes complication; a 19-year-old German who developed Type 1 diabetes five to seven weeks after a novel coronavirus infection but who lacked the antibodies commonly associated with the autoimmune disease.

Doctors at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, meanwhile, noticed an increase in the number of Type 2 diagnoses in children, as well as a severe complication of diabetes. After some of them showed evidence of past coronavirus infections, Senta Georgia, an investigator in the hospital’s Saban Research Institute, began looking deeper. Her research, which repurposes tissue from primates used in vaccine tests, is undergoing peer review.

“Only with the scientific public square can we put all of this data out there, evaluate its strengths and weaknesses … until we really get the information we need,” Georgia said