If there is no God, there may yet have been a historical Jesus. If Jesus never existed, there might still be a God. The two questions are quite different, I would say unrelated. You will certainly find many atheists who believe there was a historical Jesus and even admire him in the same way they regard, say, Confucius. They are rarer, but you can even find Christians (like Roman Catholic monk and New Testament scholar Thomas L. Brodie) who do not believe there was a man named Jesus of Nazareth who walked the earth in ancient times. This book does not consider theism and atheism, being instead devoted to the question of the Christ Myth in its many versions.

The opinion that Jesus never existed is a very old one. The pseudonymous author of 2 Peter found himself in a defensive posture when he wrote, “We did not follow cleverly devised myths when we made known to you the power and coming of our Lord, Jesus Christ, but we were eye-witnesses of his majesty” (2 Peter 1:16). He was fibbing, but that’s not my point here. Rather, it shows that at least as early as the middle of the second century CE when this pious forgery was composed, some critics of Christianity were denying the Christian savior had ever lived. Strangely, you will find that mainstream biblical scholars mount a similar argument to 2 Peter’s. That ancient author was appealing to the past to defend a historical Christ, claiming to have seen Jesus in person. In a mirror-image version, today’s scholars also appeal to ancient history in order to discredit Mythicism by claiming there were no ancient Jesus Mythicists. How odd to hear them echoing the maxim of Medieval Catholics: “If it’s new it’s not true. If it’s true it’s not new.” Such opponents of Mythicism seem to believe that, without an ancient pedigree, a theory need not be taken seriously, never mind that their own rational-critical approach to Jesus studies is a historically recent invention.

Yes, mainstream academics laugh off Jesus Mythicism, consigning it (and those who espouse it) to the same “weirdo file” as moon landing deniers. Why? Because Mythicism is indefensible nonsense? That might be so, but I cannot help understanding the situation along the lines of Peter Berger's theory of “plausibility structures,” according to which the plausibility of any notion is proportional to the number of one’s peers who believe it. The result is “consensus scholarship,” a box outside of which nothing can be taken seriously. Minority ideas will automatically appear bizarre and heretical. It is not that consensus scholars are afraid to dissent from the party line, lest they lose their jobs. No, it is more a matter of social psychology. But I am no mind reader, so I never dare try to explain away someone’s rejection of my opinion on this basis.

In fact, as Thomas S. Kuhn explains in his great book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, advances in science proceed at least as much by new paradigms for construing data as by the discovery of new data. New models, theories, and paradigms are suggestions for making new and better sense of the data we already had. These new notions must prove themselves by running the gauntlet of collegial criticism. That’s the way it has to be; you don’t want your colleagues to just accept your theory by faith. You want it to win out, so you welcome the initial skepticism. And eventually, despite their investment in traditional consensus viewpoints, your peers may be convinced, and your once-eccentric theory may become the consensus position—until some other upstart supplants it.

This is what happened with Continental Drift: once scientists dismissed it like Flat Earthism, but eventually, with the rise of Plate Tectonics, the wind shifted, and scientists reluctantly admitted that the fact that the outlines of the continents fit together like puzzle pieces was no mere coincidence. Heresy has morphed into Orthodoxy. It has also happened (many times) in the field of biblical studies. The most drastic recent instance is that of so-called “Old Testament Minimalism,” the theory that Hebrew scriptural characters were almost all mythical: not just Adam and Eve, not only Cain and Abel, Enoch and Noah, but even Father Abraham, Moses, David and Solomon. The pioneer theorist of Minimalism, Thomas L. Thompson, was forced out of a promising academic career and had to take up house painting to make a living—until the tide finally turned. Now everybody’s a Minimalist, everybody but fundamentalists, that is. And now Professor Thompson has received the recognition he deserved all along.

It turns out that the factors that led to Old Testament Minimalism (archaeological reevaluation, tradition criticism, etc.) are also operative in Jesus Mythicism, which ought, in fact, to be called “New Testament Minimalism.” I expect, or suspect, that the wheel will keep turning and that Jesus Mythicism will sooner or later gain similar acceptance—not that I'll ever live to see it. I’m not even rooting for it. To me, it’s just a fascinating subject. And I’m far from alone in this. The contributors to the present collection are creatures, eccentrics, like me. And, though we are few (at least at present), there is a surprising range of theories among us. And I think it will always be this way, because that’s the way it is in scholarship.

As you are probably aware, today’s mainstream Jesus scholarship is quite diverse. Many theories have attracted dedicated partisans, people who conclude that the historical Jesus was a revolutionist (Robert Eisenman, Peter Cresswell), a feminist (Elisabeth Schiissler Fiorenza, Luise Schottroff), a Cynic sage (John Dominic Crossan, F. Gerald Downing; Burton L. Mack, David Seeley), a Pharisee (Harvey Falk, Hyam Maccoby), a Hasidic master (Geza Vermes), a shaman (Stevan L. Davies, Gaetano Salomone), a magician (Morton Smith), a community organizer (Richard A. Horsley), an apocalyptic prophet (Bart D. Ehrman, Richard Arthur), and so on. It would be easy and tempting for an external observer to shake his head and to judge that all these Jesus reconstructions, though a pretty good case can be made for most of them, cancel each other out. If this one is as likely as the others, why choose any one of them? Well, of course, you have to look into them all (if you want to have the right to an informed opinion) and then make your own decision. But most likely it will be a tentative one—as it must be if you want to be intellectually honest. Your conviction should not be stronger than the (fragmentary and ambiguous) evidence allows.

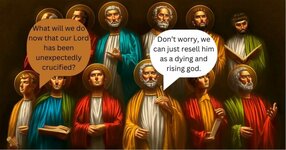

If someday Jesus Mythicism should dominate the field, I’m afraid this predicament would not change. As this book will make absolutely clear, there are just as many Mythicist theories. Some believe that Jesus was a fiction devised by the Flavian regime in order to pacify Jews who had the nasty habit of violently rebelling against Rome. Others argue that Jesus was a Jewish/Essene version of the equally mythical Gautama Buddha. Another option is that Jesus was, like the Vedic Soma, a mythical personification of the sacred mushroom, Amanita Muscaria. Or perhaps Jesus was a historicization of the Gnostic Man of Light. Was Jesus a Philonic heavenly high priest figure? And there are more. I believe you will find yourself surprised and impressed by the cogency of these hypotheses. Once you probably regarded all these theories (if you ever even heard of them!) as equally fantastic. After you've finished Varieties of Jesus Mythicism: Did He Even Exist?, you may very well find them equally plausible. And who says you have to settle on any one of them? It’s worth the mental effort to grasp and weigh each one. I say, let a hundred flowers bloom!

--Robert M. Price (2021). "Introduction: New Testament Minimalism". In Loftus; Price (in en). Varieties of Jesus Mythicism: Did He Even Exist?. HYPATIA Press. ISBN 978-1-83919-158-9.