bilby

Fair dinkum thinkum

- Joined

- Mar 6, 2007

- Messages

- 40,693

- Gender

- He/Him

- Basic Beliefs

- Strong Atheist

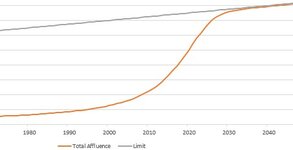

You are right; IF we assume that (for no reason you can articulate), carrying capacity is about to suddenly fall dramatically from a previously steady high level, THEN we would face disaster.Here is the representative curve of what I think we may be up against. And as I emphasize, all this changes if we come up with significantly better technology that we use or if we have a significant reduction in affluence levels. This suggests we may need a reduction in half.

That appears to be possible if we just commit to a voluntary reduction of one less birth per woman during her lifetime.

If we needed to do that, it would be very difficult to achieve, yes, but not impossible.

So what?

If my aunty had a penis, then she would be my uncle.

We should not make policy on the basis of entirely fictional future scenarios.

Not even if they are called "representative", rather than the more accurate "guesswork".

Not even if you present your guesswork in the form of a pretty graph.

What is it that happens in 2080 to dramatically reduce the carrying capacity of the planet?

How do you know that this is going to happen?

Why is your scenario more plausible than a continued steady state? Is a steady state even an accurate "hindcast" of what the carrying capacity has been since 1950?

A look at the numbers of people who died or suffered as a consequence of having insufficient access to resources, suggests that that blue line should have a very significant upward slope between 1950 and today; Steeper than the slope of the orange line. Which renders your prediction of a downslope in 2080 even less "representative" of any plausible future than it already is.

Claims that boil down to "if my predictions are correct, then they are correct, therefore we should assume them to be correct, and should make policy on that assumption" are just bad thinking.